I was introduced to the world of professional grade sound recording right before Christmas in 1971. A college friend of my father’s, Paul, took me with him to record a local community group’s performance of The Messiah at Montgomery Blair High School, in Silver Spring, Maryland. Paul brought me along with Jack Towers, several pricey Neumann microphones, and some portable Ampeg reel-to-reel recording decks. Portable in this instance meant each man had a foot-locker sized deck, along with a similar size pre-amp that had handles on the sides. Each piece required two people to carry it.

Paul could be described safely as an audio nut. In his Takoma Park basement, his hand-built home stereo included horns that had been used for early demonstrations of stereo in DAR Constitution Hall in the 1950s.

The horns provided part of his mid-range.

Paul was the official recordist of the world-renown D.C. Youth Orchestra. Soon I would accompany him regularly to the home of the DCYOP, Coolidge High School in D.C., quite often to the Kennedy Center which had opened recently, and to other events to record regional orchestral, chamber groups, choirs, and jazz. Again with Jack Towers, we recorded jazz violinist Joe Venuti at Georgetown’s Blues Alley on his final D.C. visit before a return to Italy, where he died two years later.

I already had a taste for many different types of music. I enjoyed Top 40 radio that was heavy on Motown, and was collecting Aretha Franklin albums. I would listen repeatedly to any song that provided multiple full-body orgasms, wondering how that happened. I convinced my mother to take me to Constitution Hall to see Leonard Bernstein and the N.Y. Philharmonic in August 1967 on Bernstein’s last trip through the area as the NY Phil’s conductor, and Paul took me to Constitution Hall to attend a performance by the great Russian pianist Emil Gilels. Paul was an enthusiastic opera fan and season-ticket-holder for Constitution Hall concerts, and after each piece he would place his open hand next to his mouth and shout “Bravo!” at the stage many times. I was not used to such unashamed enthusiasm.

The only pop concert I attended early on was Peter, Paul & Mary at the Carter Barron for my 13th or 14th birthday, but I only wanted to go because John Denver was opening for them. (It had been sparsely attended while afflicted with light showers.) During my mid-teens, I regularly listened to a jazz anthology series on Public Radio which had 180 half-hour episodes; they were played late nights and early mornings, and my nocturnal orientation often allowed me to hear two episodes a day. I heard most of them at least three times before it wasn’t on the schedule any longer. It was like attending my own secret jazz school. The episodes were written with emphasis on each artist’s personal story as related to their music career, and, while often tragic, many of these stories left me with a deep longing for stories of current-day musicians that felt as important and influential.

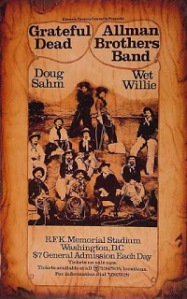

24 March 1973 found me at my first rock concert. I rode sliding, seated on the wooden floor in the back of a rented yellow Ryder truck with a bunch of hippies from school, to the Spectrum in Philly, to see The Grateful Dead. I had only heard their album American Beauty on a friend’s pitiful portable, so to suddenly experience an eight-minute Tennessee Jed and perfect 19-minute Playing In the Band through their clear-sounding JBL and McIntosh-based sound system, was rich nutriment to my hungry ears. It changed my life. When the Dead came to RFK Stadium that June 9 and 10 for a co-headlining weekend with the Allman Brothers, I had to attend both shows. I slept on the lawn at RFK with my face planted on my bandana after the first day’s show, too.

Music that was this accessible as it took one through glorious 20-minute dancing tapestries of buoyant harmonic changes, with instrumental solos and multi-layered vocals, to deliver one in a tidy package to a different place quickly seemed the obvious norm. This was what rock music could provide and did provide. Imagine my surprise when I attended a rock concert where a band played its songs more or less like their studio recordings, then were done. I felt ripped off!

For years I played drums with many guitarists and bass players in various band attempts. We rarely got out of the basement, but I took an interest in learning the sound reinforcement gear. Thanks to my grandmother, I attended Omega Recording Studios in Kensington, for basic and advanced recording engineering courses. With my longtime enthusiasm as musical omnivore and in the preservation of sound recordings, when I applied in 1990 to work as a playback technician in the stacks of the largest recorded sound collection in the world at the Library of Congress [LC], I was a natural fit. I’m confident that when my supervisor-to-be asked each candidate what we knew about the preservation of sound recordings, few others provided a 25-minute answer, and none continued for 35 meticulous minutes visiting several continents, when asked what kinds of music they were familiar with.

I had my first serious encounter with the music of Tori Amos at LC. I was becoming good friends with a 120-day temp worker. One day over lunch I asked what she seemed to be listening to all the time on her yellow sports model Walkman as she stood at the great wall of surplus sorting LPs. Upon returning from lunch, I walked several feet over to the Atlantic CD shelves and put up a copy of Little Earthquakes on the UREI main monitors, listening as I sorted baskets of incoming LPs while seated just inside the entrance to the stacks. I didn’t get a clear audition of all of it, so I put it up again the next day. That was it. I bought my own copy. Around this time, awareness of and access to the pre-web, text-based Internet were spreading around LC. I subbed to a command line UNIX shell account for personal Internet access, and managed to join the Really Deep Thoughts discussion mailing list.

Under the Pink finally came out. By this time I was relishing the ability the Internet afforded to communicate with others swept up in this music, then, weeks later, a concert at Lisner. By the time I reached the counter at the Hecht Company’s ticket department in Wheaton Plaza, they only had single tickets left. I had come for six together and bought the last six. Having read so many concert reports from others and knowing how much the music affected me, I was fearful of being too close to the stage, so I kept the ticket farthest from the front for myself, five rows from the back wall. I managed only one more concert that year when she came back in July, but before the 1996 tour began, I knew I wanted to attend as many concerts as I could. I traveled around the East Coast, then helped a friend move to Seattle that July by car, with the agreement to borrow her car when we were on the West Coast to attend more concerts. Then I flew home from SeaTac after attending my concerts numbered 9 – 18 of the tour.

I saved up enough vacation time to be able to travel to the U.K. in May 1998 for the start of the main tour, Tori’s first with a full band. The last song on Boys for Pele, “Twinkle,” had given rise to a curiosity about the Island of Iona and its Abbey, which were mentioned in the lyrics. I took the opportunity of going to the U.K. on a cheaper flight a few days earlier than I needed to for the concerts, and spent four days at Mrs. Black’s B&B at Clachan Corrach on the Isle of Iona. The six concerts I attended in the U.K. helped me set a baseline for the early band shows. This allowed me to apprehend the progress made later in the summer when they developed a serious group-think proficiency. Finer points of this band became real to me by the  end of the tour, when I attended 19 of the last 20 concerts. Such satisfying music—each musician and crew member was top-notch, knew why they were there, and all of them did their jobs with personal flair, even the riggers. I felt privileged to be able to experience the full scope of that tour, and to meet many others with so much dedication to the music. A year plus tens of thousands of miles later, all of it in my faded red 1987 Chevy Nova, I wrote something and posted it to the Precious Things mailing list that inspired a friend to ask if I ever considered writing a book on the music.

end of the tour, when I attended 19 of the last 20 concerts. Such satisfying music—each musician and crew member was top-notch, knew why they were there, and all of them did their jobs with personal flair, even the riggers. I felt privileged to be able to experience the full scope of that tour, and to meet many others with so much dedication to the music. A year plus tens of thousands of miles later, all of it in my faded red 1987 Chevy Nova, I wrote something and posted it to the Precious Things mailing list that inspired a friend to ask if I ever considered writing a book on the music.

Thoughts on Providence, 10/30/99

I think he expected I would mainly write a book for fans to buy, but he never said, and in the contract we would sign nearly a year later, I have full control over editorial content. I wanted to write something more meaningful and with broader appeal than that. I kept thinking of something one of my favorite bosses at LC used to tell me was the main thing to convey when writing a book on an artist: “What does it mean?” He always told me to not simply catalog and describe the work. I wanted to know why I’d extended myself so much to attend as many concerts as I had, stretching limits of body, car, wallet, and the comprehension of my non-Tori friends and family. What in the music does this? Is it something in “the music itself” that does it? Is it a combination of the ecological ingredients involved in attending concerts including the travel, venues, conversations, Internet? Is it the knowing looks shared from the stage? While all those things figure into the answer to the question “Why?” the music is clearly the dominant factor. What in the music causes such strong personal emotional responses? How does that work, and what can anyone interested in creating, performing, or experiencing great art of any kind do to foster deep, even primal resonances in themselves?

Tori Amos music is singular, but the aural and psychological landscapes of how her music works aren’t. I intuitively knew that brain science and the nervous system would explain some of this stuff, but not all. I knew the lessons of Carl Jung were important to Tori, and that they must have helped steer her approach to songwriting and performance, so I needed to learn some Jungian theory. I read some canonical books on music and medicine and the brain, then read some which were recently published. I sought guidance on learning Jungian thought from the librarian at the Jung Society of Washington. I still attend lectures and classes they put on, at least I have as recently as 18 months ago. Two years ago I attended an eight-week course at the Jung Society entitled Dreams and Active Imagination. The analyst who taught the course granted me an exemption from bringing a dream into class on which to perform Active Imagination, allowing me to share a song instead. I presented the most mystical Tori Amos song: “Sister Janet.”

Over the years I always let my nose and ears tell me what area or discipline to study next. I felt as if I were in a graduate degree program without any advisors. I had to figure out everything by myself from scratch. I went down a few worthless hallways, but only a couple minor ones. A person here and there could advise me in general ways in their area of expertise, but really, I was almost always entirely on my own. I read more than 200 books for this project. I did genealogy research off and on for many years, including trips to eastern Tennessee where Tori’s beloved grandfather came from, and where her storied ancestor Margaret Little lived and died. I took a music course at Montgomery College, and attended lectures sponsored by the Smithsonian on many topics. I studied music theory, mythology, Joseph Campbell, fairy tales, mermaids, neurology, brain science, memory, charisma, literature, writing, acting methods, the means by which a variety of keyboard instruments operate, slavery in the ivory trade in Africa and New England and how the piano industries were reliant upon it—a literal bloodline of the piano, a great deal on the Cherokee and other First Nations peoples, including trips to the Carolinas, and to the American Philosophical Society Library in Philly where they have major collections on tribal peoples, including many historical sound recordings of the spoken Cherokee language.

My mother developed serious trouble walking and standing in April 2001. Soon she was sleeping in a hospital bed in her living room, and along with home health workers who stopped by several times per week, I was taking care of her. I got her some outpatient appointments at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, but they weren’t sure what was wrong with her. After six months under this arrangement, the home health nurse said if a woman wasn’t going to take care of my mother day to day, she would have her sent to a nursing home. My mother’s remaining sibling, her older sister, agreed to take charge of my mother. A new tour was about to begin in Florida. 9/11 happened. As agreed, in late September 2001, I took my mother to southwestern Virginia and stayed with her a couple days at my aunt’s, then I picked up a friend near Charlotte and continued to the first tour stop in Florida.

We managed nearly three weeks on the tour and picked up an old tour companion in New York City, but I eventually needed to return home due to circumstances of others. My father had died in a Texas hospital that summer, and although we hadn’t spoken in a few years, I received a posthumous gift from him some weeks later. Having begun the tour and savored its glory, I was spurred to head west to finish the U.S. leg of the tour. An old friend in Philly agreed to come with me. I picked him up and we headed to Oakland. My mother’s health continued to decline slowly at her sister’s, and she was completely bedridden for many years. I came to spend increasing amounts of time there. Coincidences of geography allowed me to continue research from time to time, but I was nearly done with anything I set out to research, and was waiting to be able to get my living environment set up with my research materials where I could easily access them, in my own increasingly mobility-challenged condition.

Days after my mother died nearly three years ago, I went to a long-standing appointment in Baltimore with Johns Hopkins’ Neurology Department. Several Hopkins visits led to my diagnosis of multi-level disk degeneration. I don’t have much control over the muscles in my lower legs. I can only walk short distances even using two canes or a rollator. I began looking for trustable people to help me clean out my mother’s house, move me to a larger house with fewer stairs, and help get my research materials and personal effects organized so I could set about writing my book in earnest. Most of my helper friends could not come to my new house as often as I wanted and the organizing process was lengthy, and now I find myself out of cash.

In addition to having so much experience of the music, I did a ton of research on this book project across many disciplines, and have things to report that are my own. I am a strong Mercury/Hermes Archetype personality, which I came to realize only after Tori told me I was Mercury in Manchester in May of 1998. Perceiving how things are connected when others don’t and changing people’s thinking are major aspects of my personality. I want to affect the way music is taught with this book, and am planning to market it heavily to music teachers in addition to Tori Amos people. Examples I have gleaned from studying the life and music of Tori Amos have taught me techniques and methods anyone can learn to increase their ability to compose, perform, and listen to music at a soul level. These things embrace the fact that we can simultaneously experience ourselves, and feel more invested in the human community.

I want to affect the way music is taught with this book, and am planning to market it heavily to music teachers in addition to Tori Amos people. Examples I have gleaned from studying the life and music of Tori Amos have taught me techniques and methods anyone can learn to increase their ability to compose, perform, and listen to music at a soul level. These things embrace the fact that we can simultaneously experience ourselves, and feel more invested in the human community.

I estimate I will need a good six months more to finish the writing-editing process and go to print. My friend and initial investor who suggested a book will cover the various costs of printing when that time comes. I need to raise money for all my living expenses until I finish writing the book. If I am unable to continue living in this house which is set up for me to write even though I have mobility problems, it may be that years of research I’ve done will go to waste. I want to share what I’ve learned, and I’m confident many people want to read it. All I know to do is to throw this project and myself to the tender mercies of the music and Tori Amos communities. I’ve continuously demonstrated my refusal to give up on this project, but my current investors can only support me to a point, as they have their own families and other responsibilities to tend. In 20 active years online, I’ve taken great pains to avoid sharing much of my personal life publicly. This is nothing I would choose to do were it not my only hope for getting this book finished. I’m asking for your support and assistance in promoting this crowdfunding campaign.

Thank you.

Richard Handal

Return to the BE THE MUSIC page on Authr.com